Is Democracy Mathematically Impossible? Unveiling the Complexities of Voting Systems

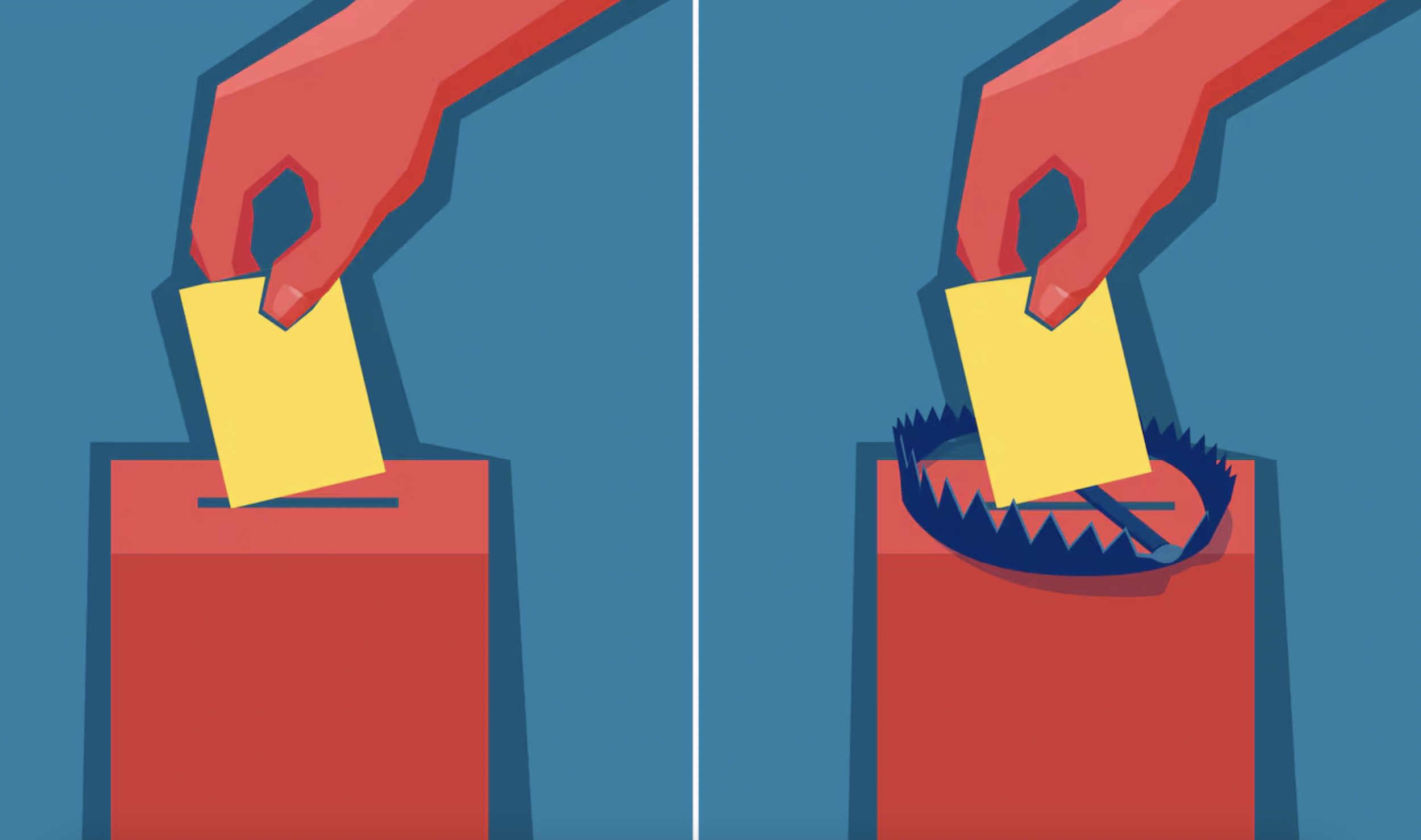

Here, we explore the mathematical challenges and paradoxes within voting systems, questioning whether true democracy can be achieved due to inherent complexities in accurately representing the will of the people.

In the age of modern governance, democracy is often celebrated as the pinnacle of fair representation. However, a lesser-known, yet profound, mathematical reality casts doubt on the very mechanisms we use to elect our leaders. This isn’t a critique of human nature or an observation about the instability of democratic societies throughout history; rather, it’s a reflection on a well-established mathematical fact. Our current methods of electing leaders, primarily through voting systems, are fundamentally irrational. This video explores the math that substantiates this claim—a discovery so significant it led to a Nobel Prize—and delves into the intricacies of how groups make decisions and the flaws inherent in our voting systems.

First-Past-the-Post Voting: A Historical Overview

One of the simplest and most widely used methods for holding elections is known as first-past-the-post (FPTP) voting. In this system, voters select one candidate as their favorite, and the candidate with the most votes wins the election. Despite its simplicity, FPTP has significant flaws that can lead to undemocratic outcomes.

FPTP has deep historical roots, dating back to antiquity, and has been used in England to elect members of the House of Commons since the 14th century. Today, 44 countries, including many former British colonies such as the United States, still use FPTP to elect leaders. However, the system is problematic. For instance, it frequently results in situations where the majority of a country did not vote for the party that ends up holding power. In the UK, over the past 100 years, there have been 21 instances where a single party held a majority of seats in Parliament, but only twice did that party actually receive a majority of the popular vote.

The Spoiler Effect and Strategic Voting

The FPTP system also exacerbates the problem of similar parties splitting the vote, which can lead to the unintended election of a less popular candidate. This phenomenon is known as the spoiler effect. A notable example occurred during the 2000 U.S. presidential election. The race was primarily between Al Gore and George W. Bush, with Ralph Nader running as a third-party candidate. Although Nader garnered only a small percentage of the vote, his presence on the ballot likely influenced the outcome. In Florida, Bush won by a mere 600 votes, while Nader received nearly 100,000 votes. Many Nader voters would have preferred Gore over Bush, but because FPTP only allows voters to choose one candidate, they inadvertently contributed to Bush’s victory.

This system often forces voters to cast their ballots strategically rather than sincerely. If a voter believes their preferred candidate has little chance of winning, they may choose the lesser of two evils among the more viable options. This dynamic inevitably leads to a concentration of power in larger parties, often resulting in a two-party system—a phenomenon so common that it is known as Duverger’s Law.

Alternatives to First-Past-the-Post

Given the flaws of FPTP, what alternatives exist? One option is a system where a candidate can only win if they secure a majority of the votes. If no candidate achieves this, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and a new round of voting begins. This process continues until one candidate obtains a majority. However, holding multiple elections is cumbersome, so many propose a more efficient method known as instant-runoff voting (IRV), also called preferential or ranked-choice voting.

In IRV, voters rank candidates in order of preference. If no candidate receives a majority, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and their votes are redistributed based on the voters’ next preferences. This process repeats until a candidate secures a majority. While IRV mitigates some issues inherent in FPTP, it is not without its own problems.

The Condorcet Paradox and Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem

The French mathematician Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, known as the Marquis de Condorcet, was one of the pioneers in applying mathematical rigor to the study of voting systems. He proposed a method where the winner is the candidate who can defeat every other candidate in a head-to-head contest. However, Condorcet’s method is not foolproof. It can result in what’s known as the Condorcet Paradox, where no candidate is the overall winner because of cyclical preferences. For example, if three friends are choosing between burgers, pizza, and sushi, they might collectively prefer burgers to pizza, pizza to sushi, and sushi to burgers, creating a preference loop with no clear winner.

Condorcet’s paradox remains unresolved, but his work laid the foundation for further exploration into the complexities of voting. In 1951, economist Kenneth Arrow published his groundbreaking Ph.D. thesis, which introduced Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem. Arrow outlined five reasonable conditions that any fair voting system should meet: unanimity, non-dictatorship, unrestricted domain, transitivity, and independence of irrelevant alternatives. However, Arrow proved that no ranked voting system could satisfy all these conditions simultaneously when there are three or more candidates. This revelation shook the foundations of social choice theory and earned Arrow the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1972.

A Comparative Insight: Federal vs. Commonwealth Voting Systems

Federal and Commonwealth voting systems in democratic nations offer distinct approaches to electoral processes, each with profound implications for governance and representation. In federal systems like that of the United States, the electoral process is inherently decentralised, granting individual states significant autonomy over how elections are conducted. This decentralised structure means that each state can establish its own rules and regulations, resulting in a patchwork of voting laws across the country. Variations can include differences in voter registration processes, the accessibility of early voting, the use of voter identification laws, and the procedures for counting and verifying mail-in ballots. This system’s complexity often leads to disparities in voter access and participation rates, depending on the state.

On the other hand, Commonwealth nations, such as Australia and Canada, typically employ a more standardised and centralised approach to elections. In these countries, electoral laws and processes are usually governed by a central electoral commission, which ensures uniformity across the nation. For example, in Australia, the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) oversees the electoral process, ensuring that voting procedures are consistent in every state and territory. This centralised approach can lead to a more straightforward and transparent voting process, reducing confusion among voters and ensuring that electoral outcomes more accurately reflect the will of the entire electorate.

The differences between these systems become particularly evident during high-stakes elections. Donald Trump’s first presidential campaign in 2016 serves as a prime example of how the U.S. federal system can influence electoral outcomes. Trump’s campaign strategically focused on winning key swing states, where the outcome was uncertain and could tip the balance of the Electoral College in his favor. This strategy proved successful, as Trump secured the presidency despite losing the popular vote by nearly three million votes. The Electoral College, a uniquely federal institution, played a pivotal role in this outcome, underscoring how the structure of the U.S. voting system can sometimes produce results that diverge from the national popular sentiment.

As the United States gears up for its 2024 elections, the influence of its federal system remains a critical factor. Candidates are once again tailoring their campaigns to target specific battleground states, aware that victory in these areas could be decisive. The ongoing debates over voting rights, voter suppression, and election security are deeply intertwined with the federal system’s decentralised nature. These issues are likely to shape not only the 2024 election but also the broader discourse on the future of American democracy.

In contrast, Commonwealth nations tend to avoid such disparities in representation due to their more uniform voting processes. In Australia, for instance, the use of compulsory voting and a preferential voting system helps to ensure that the elected government reflects the preferences of a broad cross-section of the population. The centralised administration of elections also means that there is less opportunity for regional disparities in voting laws, leading to a more cohesive and representative electoral outcome.

The contrast between these two systems highlights the broader implications for democracy in different political contexts. In federal systems, the tension between state autonomy and national cohesion can lead to complex electoral dynamics, where strategic campaigning and regional issues play an outsized role. In Commonwealth systems, the emphasis on uniformity and central oversight seeks to create a more equitable and straightforward electoral process, though it may also limit the flexibility that federal systems provide.

As global political landscapes continue to evolve, the comparative study of federal and Commonwealth voting systems offers valuable insights into the strengths and challenges of different democratic models. The upcoming U.S. elections in 2024 will once again put these dynamics on full display, offering a real-time case study of how federalism shapes electoral strategies, voter engagement, and ultimately, the functioning of democracy itself.

Democracy, Going Forward

Arrow’s theorem suggests that a perfect voting system is impossible, at least within the framework of ranked-choice voting. However, mathematician Duncan Black offered a more optimistic view. He demonstrated that if voters and candidates are aligned along a single dimension—such as a liberal-to-conservative spectrum—the preference of the median voter will typically determine the outcome, avoiding the paradoxes highlighted by Arrow. This finding suggests that while democracy is not without flaws, it may still be capable of reflecting the majority’s will in certain contexts.

Moreover, Arrow’s theorem applies specifically to ordinal voting systems, where voters rank candidates. There is another class of voting systems—rated voting systems—that may offer a solution. In these systems, voters rate candidates on a scale, and the candidate with the highest overall rating wins. One example is approval voting, where voters simply indicate which candidates they approve of. Research has shown that approval voting can increase voter turnout, reduce negative campaigning, and prevent the spoiler effect.

Approval voting is not a new concept; it was used by the Vatican to elect the Pope between 1294 and 1621 and is currently employed to select the Secretary-General of the United Nations. While it hasn’t been widely adopted in large-scale elections, its potential benefits suggest it warrants further exploration.

So, is democracy mathematically impossible? The answer is nuanced. While Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem reveals the inherent limitations of ranked-choice voting systems, it doesn’t condemn democracy as a whole. Different voting methods, such as approval voting, offer promising alternatives that could address some of the flaws in our current systems. Despite its imperfections, democracy remains the best system we’ve got for representing the will of the people. As Winston Churchill famously said, “Democracy is the worst form of government except for all the others that have been tried.” The challenge lies in continuing to refine and improve our democratic processes to better serve society.

As the world changes, so too must our approaches to governance. The flaws in our current voting systems are not reasons to abandon democracy but rather to innovate and adapt. The game may be crooked, but it’s the only game in town—and it’s worth playing.